Did someone forward you this? Subscribe here free!

Good morning, Roca Nation. Here are today’s four need-to-know stories:

Netflix agreed to purchase Warner Bros. Discovery's film studio, television production, and streaming operations

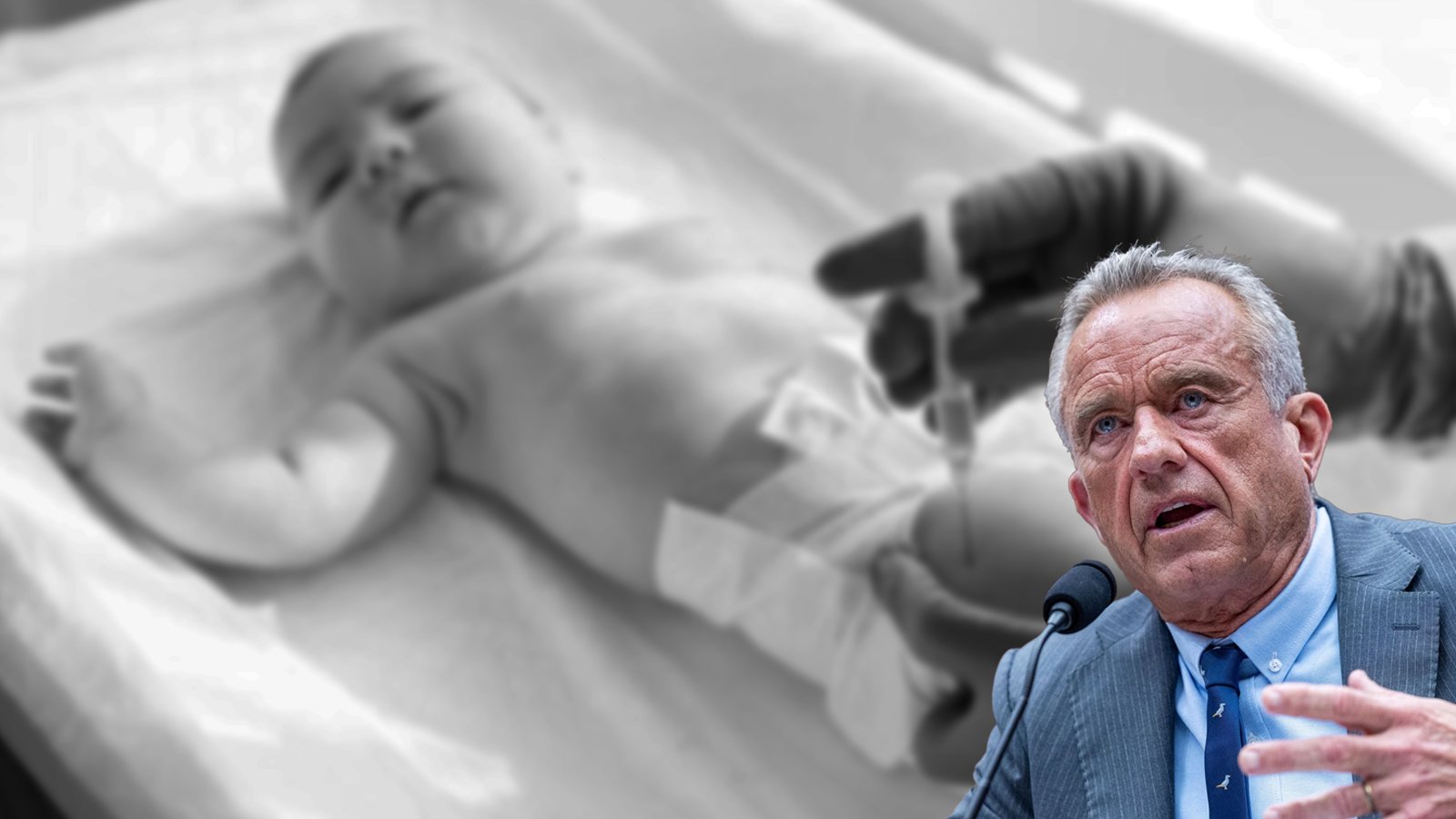

A federal vaccine panel voted to eliminate a recommendation that all newborns receive hepatitis B shots (free)

Four European countries announced they would boycott the 2026 Eurovision Song Contest after organizers allowed Israel to continue competing (free)

The Trump Administration released its National Security Strategy

By Rob McGreevy and Max Frost

It’s not everyday that business deals have an obvious impact on us average people. The deal announced by Netflix on Friday is different.

The world’s largest streaming service is buying Warner Bros., one of the most valuable legacy film companies, for $83B. One of the biggest media deals in history, it means that Netflix will now own all Warner Bros. film assets, Warner Bros. studios, and HBO, including its streaming service HBO Max.

There’s two backdrops we could explore in a deep-dive about this.

One is about the streaming wars: The acquisition signals the long-predicted consolidation of the media market, as legacy players and streamers compete for content and eyeballs. Netflix’s acquisition of Warner Bros. will have far-reaching implications on this and how other companies merge in the future.

Yet there’s another, perhaps more important backdrop, and that considers monopoly power in the modern world.

Today’s tech companies exercise levels of wealth and power like few companies before them. Consider Netflix: Its market capitalization is more than double that of Disney, which owns not just Disney media assets but ESPN, Hulu, parks, and much more. With its takeover of Warner Bros., Netflix will now remove HBO Max from its list of competitors.

Or will it?

The answer may lie with the Free Trade Commission (FTC), a bland-seeming government body with tremendous influence over the economy. In today’s deep-dive, we look at the FTC, its power, and why it may or may not prevent Netflix’s takeover of a major rival.

The FTC has its roots in a president who hated monopolies: Teddy Roosevelt.

At the turn of the 20th century, Roosevelt was increasingly alarmed at the power held by John D. Rockefeller, America’s first billionaire and the baron of oil giant Standard Oil.

Rockefeller’s strategy was to buy up the nation’s railroads and Ohio’s oil refineries, then merge it with his ownership of oil wells. One of the first and most prominent examples of vertical integration, it resulted in Rockefeller owning 90% of the refined oil business in America. Competition didn’t seem possible.

Standard’s stranglehold prompted Roosevelt to sic both the Bureau of Corporations and the Department of Justice (DoJ) on it in an attempt to break up the conglomerate. In 1906, the DoJ filed a lawsuit to dissolve Standard Oil; in 1911, the Supreme Court ruled in Teddy’s favor, smashing the Standard monopoly to bits and scattering the pieces into the wind.

The court divided Standard and its subsidiaries into 34 companies, many of which remain giants today: Standard Oil of California became Chevron, Standard Oil of New Jersey became Exxon, and Standard Oil of New York became Mobil.

That ruling would pave the way for the debate today.

Three years later, the Federal Trade Commission Act established the FTC. With a slogan of “protecting America’s consumers,” its task was twofold: Enforcing antitrust laws and consumer protection.

Since 1998, the FTC has increasingly clashed with Big Tech.

That year, the FTC sued Bill Gates’ Microsoft for allegedly illegally monopolizing web browsing by making it next to impossible to uninstall Internet Explorer in favor of other browsers like Netscape. In that instance, the federal district court sided with the FTC, only to have an appeals court overturn much of the case and produce a weaker settlement. The resulting back-and-forth between trust busters and tech giants has continued right up until today.

In recent years, and particularly under the Biden Administration, the FTC has become more aggressive in trying to stop mergers and acquisitions that it considers anti-competitive. This has typically produced a left/right divide: People on the left want a more aggressive FTC, fearing that merged corporate power harms competition and consumers; people on the right have traditionally wanted a freer market, believing that a hands-off FTC enables investment in new companies and helps their growth.

Debates around Big Tech exemplify this. Consider Meta.

Many FTC hawks believe that Meta has too much power and faces insufficient competition, and therefore want it broken up. Creating a competitor is effectively impossible, they say, because Meta will just buy it up or beat it. FTC critics would argue that Meta will lose its power if it abuses it or allows its products to deteriorate. Just look at the rise of TikTok and YouTube Shorts to see that competition remains.

Increasingly, though, this isn’t a left-right divide.

Biden-era FTC Chair Lina Khan was one of the most aggressive FTC chairs in decades and spearheaded numerous antitrust efforts, including successful attempts to quash planned mergers between grocery giants Kroger and Albertsons and design software companies Adobe and Figma. Khan’s presence had a chilling effect on mergers, with her telling The Wall Street Journal in January, “Certainly what we heard from those in Silicon Valley and executives was that there was greater awareness that there was now a cop on the beat.”

Many populist, anti-corporate Republicans supported her.

“You are a brilliant woman with a tremendous ability to impact how consumers are going to interface with the digital world for a long time to come,” former Congressman Matt Gaetz (R-FL) told Khan in a 2023 House Judiciary Committee hearing.

Steve Bannon, Trump’s former chief strategist and a leader of the MAGA movement, has been effusive about Khan: “I think Lina Khan is one of the more important political figures in this country, and I think if she had been listed to more by Democrats they would actually have been more competitive against us in November of 2024,” he said in April.

“There's no competition for Google. There's no competition for Facebook. There's no competition. Amazon destroyed half the small business of this country, flooding the zone with Chinese Communist Party product. There's really no competition to X or to Twitter because we let 'em go,” Bannon said.

Yet to date, those pro-Khan views have held limited sway in Trump’s administration, which has thus far been anti-regulation and has abandoned the hawkish antitrust policies of the Biden Administration.

Trump hasn’t yet commented on this deal. On Friday, though, CNBC reported that the White House has “heavy skepticism” about the Netflix deal.

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos, meanwhile, said he is “highly confident in the regulatory process.”

“This deal is pro-consumer, pro-innovation, pro-worker, it’s pro-creator, it’s pro-growth. And our plans here are to work really closely with all the appropriate governments and regulators, but [we are] really confident that we’re going to get all the necessary approvals that we need,” he said upon announcing the deal.

There are many people who will certainly try to get Trump to stop the deal.

Potential opponents include Hollywood studios, who fear competition with Netflix, and other streamers, who fear Netflix pulling ahead. Some conservatives may oppose the media power that Netflix could possess; many liberals are certain to fear that Netflix will use this to weaken workers and raise prices.

Until Netflix announced the deal, the frontrunner to buy Warner Bros. was Paramount Skydance, the recently-formed media company owned by the Trump-supporting Oracle heir David Ellison. Ellison had said that Paramount’s acquisition of Warner Bros. was necessary to create a company that could compete with Netflix. Now, Netflix is pulling ahead.

Yet many believe the deal presents a risk not to society or competition, but to Netflix itself: The company’s stock dropped 3% the day after announcing the deal, as investors worried about Netflix’s ability to integrate a massive Hollywood studio whose operations will be very different from its own. Netflix’s co-CEO said himself this October that media mergers “don’t have an amazing track record over the history of time.” For context, Netflix has never paid more than $700M for a company, saying it prefers to “build, not buy.” This deal is valued at $83B.

For a warning sign, Netflix investors need look back only to 2018, when AT&T took over Time Warner, including HBO and Warner Bros., after an antitrust uproar. The merger failed, and AT&T ultimately spun off the media assets into Warner Bros. Discovery in 2022.

So perhaps the merger will be blocked; perhaps it’ll be allowed and tighten Netflix’s grasp on our media diets and budget; or perhaps it’ll be allowed and fail. Whatever happens, expect the FTC to play a part.

Editor’s Note

Should Netflix be allowed to acquire Warner Bros.? Are you worried about the tech giants’ power? Let us know by replying to today’s email.

Thanks to those who wrote in yesterday about our on-the-ground report on the National Guard in DC. Here are a couple of those replies from our DC-area readers.

Ben from Maryland wrote:

Anybody who has traveled through all of DC knows there are certain areas you want to avoid. Mainly South East and South West although they have developed a lot of the South West side over the past 20 years. I guess that just pushed more of the crime over the river. It's definitely had an effect on the crime rate in PG county in Maryland. Prince George's County had 111 murders last year compared to 201 in Baltimore (just the city). As an Independent I usually listen to both sides, do a little digging of my own, and then form my own opinion. One of them has been blue state crime vs red state crime. I couldn't help notice when you listed the red states high in crime. You also listed the Democratic controlled cities in those red states responsible for the majority of the crime. My own independent opinion is Democrats are not doing very good job at keeping their cities or states safe. The soft on crime approach only benefits the criminal and does not deter crime. Honestly it actually encourages it because the criminals know they wont receive much of a punishment if caught. Baltimore's new DA started taking the opposite approach and is not being soft on criminals sentencings. What's the result, lower crime rates in Baltimore.

And Rose said:

I've lived in DC for a long time before recently moving to VA during the pandemic. I still work in the District so am there 3-4x a week.

The reason I left DC was the crime. It was brutal, and I didn't live in Ward 8/Anacostia. Cars were broken into everyday on my street in NE and needles were found all over playgrounds.

I think the people that dont want to accept the National Guard in DC don't want to face how bad it can be over political views. My company recently issued a safety alert to pay for lunches with cards since an employee was robbed by trying to pay in cash. In broad daylight. In downtown DC. The crime is terrible and cannot be disputed.

I can't say if crime has gone down but it can't hurt them being here.

Love you guys! Keep it up.

And if you want to catch up on our latest stories, check them out below:

Thanks for reading, and see you tomorrow.

—Max and Max